Naming Homosexuality in Francophone Africa

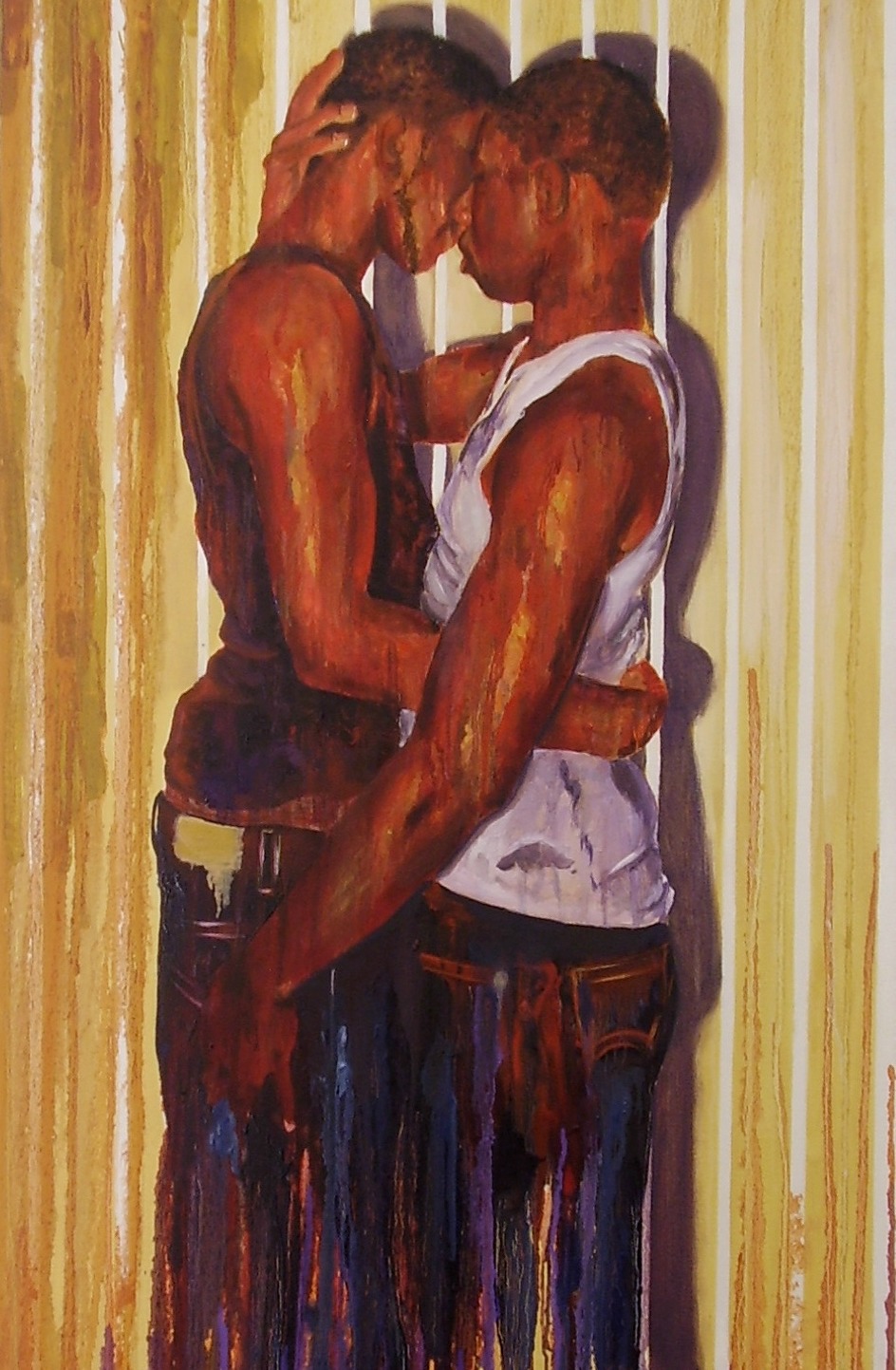

By Charles Gueboguo. Photo by Soultga and Alaasafei

Words are the opium of humanity. When they speak, they make sense everywhere. How do you say, briefly and locally “homosexual” in a place where homosexuality is most often little understood and not accepted? The focus of this paper is to explore this question in the Francophone African countries I visited. There were: Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ivory Coast and Senegal.

During my stay in Burkina Faso, I learn that in one of the main local languages, Moré, ‘homosexual’ and therefore ‘homosexuality’ is called “pouglindaogo”. Literally: man and woman together. There is a reference to hermaphrodites.

By extension “pouglindaogo” means the effeminate man. Socially, we believe that it has two biological sexes. This name seems to be a form of therapeutically explanation of what appears to be strange /foreign. “Others” are the ones who will label gay people with such word and the latter take it as an insult. In Dioula, another local language, to talk about homosexuals in a negative term, people say “Tchiété Moussoté.” But I also noted that young people use the French words to indicate homosexual behavior. In the gay community, men who play both the insertive and receptive role are called “double sided”. The relationship in representations of individuals that associates homosexuality with effeminacy is clear here. I do not remember a term for women who have sex with other women. In the imagination of many, homosexuality can only be male. It is thus rejected because it disturbs the barriers of genre. Hence, the emphasis in popular culture to reduce the reality of homosexuality to the physical aspect of the practice, and to effeminate it.

In the gay community in Cameroon, male homosexuality is translated as “nkouandengué.” This is a new word whose main existence has no other purpose than to camouflage the practice from people outside of the community. The male partner who plays the dominant role during sexual intercourse is called “koudjeu!” This is onomatopoeia, which is the expression of manhood. In French, it would mean “ho-hisse!”. It is the cry that men make when they are lifting heavy loads. The “koudjeu” is this individual who would be able, sexually speaking, to generate such a force, so much energy to bring the receptive partner into experiencing explosive orgasms. Partners who can play both roles in the sexual act are “both sides” or “skirt”. The dominant model in this sexual identity construction seems to derive its source from the dominant male in heterosexual world. Female homosexuality is translated by the word “mvoye”, in Ewondo language and means “good”. “Mvoye” is the translation of what is right and by extension, lesbians would mean to their detractors that they are part of a sexual orientation that can not be anything other than something that is wonderful, even paradise.

The language system of young gay men in Côte d’Ivoire is based on slang they call “nouchi” lively mixture of French and Negro local languages. Homosexuality is also told here through the split passive / active, which is derived from a heteronormative model. The insertive or active partner is “yossi” while the receptive or passive partner is “woubi.” These two expressions are deformations of Senegalese Wolof words “Yossi” and “Oubi” which reflect the same in the homosexual community in Senegal. The partner who can play both roles in the sexual act is called “cassette”. This designation is intentional, because as the object itself, this partner can play both sides, meaning being both the active and passive sexual partner. A “cassette” is not a bisexual. In the middle are bisexual say “yossi famo” a gayfriendly person is called “famo.” Lesbians are referred to as “toussou Bakary.” “Toussou” in the local language means a girl. The transvestites are called “contemporary women.”

The active partner is called in Senegal “Yossi”. The receptive partner is a “Oubi” in Wolof means “open.” It would therefore be “open” as would be the labia and by extension, as would a woman. This association is based in a feminine form of the social environment surrounding homosexuality, which synthesizes femininity. This is the translation of “gor-jigeen” which literally means “male/female” and akin to an insult. The homosexual would not be a separate entity but an odd thing in between, a social identity as a woman in a man’s body. There is also a link associate with age in the connotation of homosexuals, expressing the pressure of the older, more affluent partner over the less affluent and young partner. They are referred to as “maamar.” Most young people who often do not have money are called “Mbéré” and socially expected of them to play the passive role.

The categories identified here, how they identify themselves or how others identify them, have their way of saying homosexuality. For some, this will be the mode of stigma. Homosexuality will designate the male-female or intersex: necessarily pejorative in social representations. For others, it will be the mode of a need for revaluation. Identifying oneself as female, the real, while the biological organes would only be impostures. Claiming one’s femininity becomes a position of power and domination. It is therefore a double male domination that invests and colonizes the arena once reserved and exclusive to the female in order to reclaim it. Masculinity, when called in all these environments also refers to a relationship of superiority and hence of symbolic domination. The model of the heterosexual men over women is taken and assumed. The insertive partner can only be that the “koudjeu”, the “yossi”, or “Yossi”, the manly partner capable of Herculean sexual prowess. Because they are the dominant partners, in Senegal “Yossi” rarely consider themselves as gay. They also often have sex with partners of the opposite sex. And the designation “goor jigeen” is rarely addressed to them. Here, masculinity is synonymous with breath and power, symbolized by the vitalizing sperm.

The linguistic content is organized in modes that revolve around the expressive function, necessarily carrying the brand of the subjectivity of its authors, the referential function: homosexuality in these discourse appear as something strange for some. Indeed within the dominant culture, it can only express, in the register of popular culture as strange, foreign. For others it will be designated on the model of revaluation, the subject of a concrete decision to be an actor of one’s own freedom. The meta-linguistic function: The interlocutors make sure they use the same codes, the same vocabulary or the same syntax: “Kouandengué”, “toussou Bakary”, “Yossi” “goor jigeen” … It is the demand of empathy, that is to say the complicity between the transmitter and receiver based largely on the involvement of all collective imagination in force within the group.

However, because the categories are intended to speak to each other, these designations are interconnected in that they rely on feedback. They are thus linking social. What may appear as conflicts based on language form the basic of a social dynamic and the unity of sociation, that is to say society understood as a process, not a ready-made building. The effects of these designations, both within and outside the homosexual community are the same. Some like the others try to encourage changes in thought patterns and perceptions. The designations also say the real socio-sexual lived more or less sublimated in order for homosexuals, for example, to bring to existence a long invisible category: through the product of a constant tinkering to dock or circumvent normatively. Saying homosexuality is therefore bringing it into live. The same way as naming or denouncing something is to simply giving it a reality. We can only denounce what is real, we can only said what we want to rationalize.