Whether the Lion Wakes Up or Not

A conversation between Régis Samba-Kounzi & Michael Kémiargola. Photos by Régis Samba-Kounzi. Translated into English by Abdou Bakah Nana Aichatou

Régis Samba-Kounzi is a longtime LGBTI activist and a photographer in his soul. Active, discreet, and moving, he works with a rare talent and sensibility around the issues of identities, mainly: sexualities, gender, class, race, and parenthood. He lives between Paris and Kinshasa. Here he shares with us his latest project, Lolendo, about the lived realities of LGBTI persons in Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Véronica & Jeannette, Limete district, Kinshasa/DRC, 2015: “18 both, and as many LGBTI of Kinshasa, they now prefer to practice their faith among the Raelians who are open to homosexuality to avoid stigma. In the Congolese context religion is used to express one’s hatred of the others and of the difference be it in the traditional Christian churches or in the very popular and influential revivalist churches which convey an ubiquitous homophobic and transphobic and incredibly violent speech; it is therefore difficult to put one’s identity side. The need for a secure LGBTQI inclusive space has become vital for people who want to live their faith and spirituality in peace. “

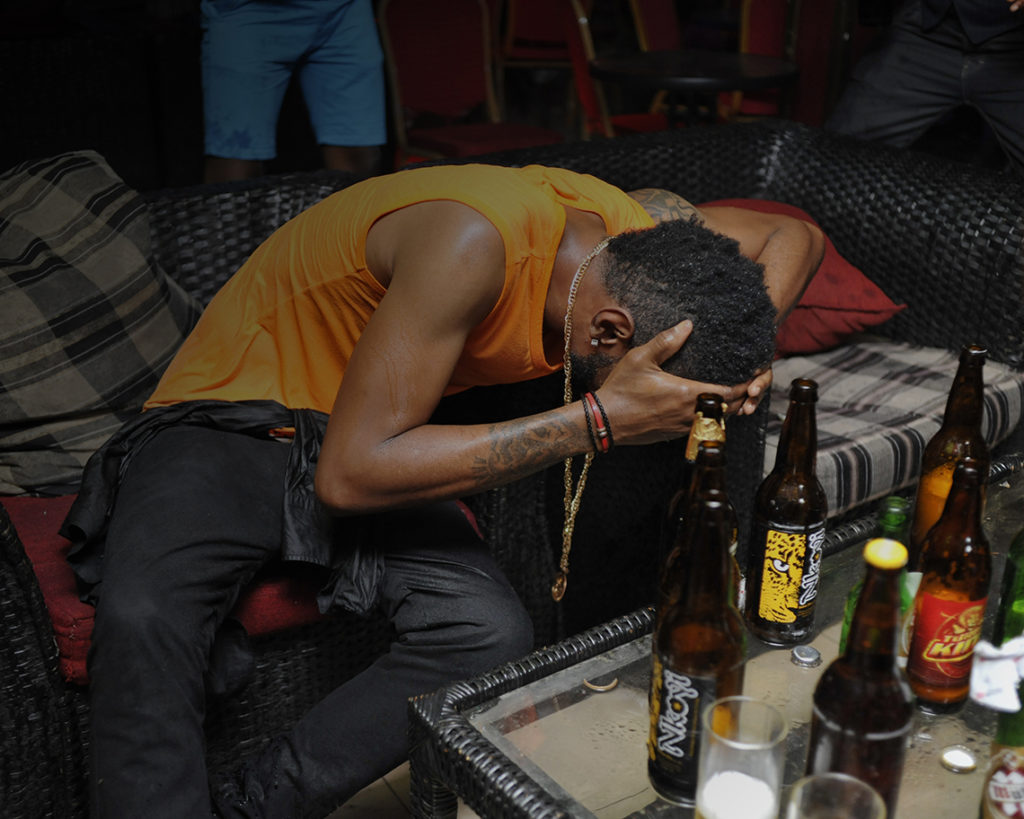

A night club of the capital, Kinshasa/DRC, 2015: There are many festive establishments in the DRC, they are intended for the heterosexual public but they are open and frequented by many gays and transgenders.

Michael Kémiargola: When and how did you get the urge to do the Lolendo series in the DRC?

Régis Samba-Kounzi: It is a project that dates back from a long time. It was born from a question I often asked myself: why when photographic works were documenting the lives of sexual and gender minorities in other countries this was not the case in the DRC, particularly in light of the increasing homophobic and transphobic climate in the country? Yet this is a subject that speaks of our time. It was an obvious subject to me so I took the challenge. I finally told myself that I had to do it, we should not wait for things to be done by others, and after all who can talk about our realities and problems better than us, the first concerned.

Belinda, Bandalungwa district, Kinshasa / DRC, 2015: “Saying that lesbians do not infect themselves seems necessary and sufficient. However, this statement is false and immediately closes the door on any discussion about prevention and health among lesbians. Fighting against discrimination, against subjugation to a patriarchal and homophobic society remains necessary because they are in part reasons why the lesbians escape the prevention speech. “

Moreover, I wanted to enlighten where noone wanted to watch and silence those who say that homosexuality never existed on the African continent, or that it is the Westerners who allegedly imported it. We know little about our history simply because it is not taught, not transmitted. There was a real brainwashing that made us believe today that gays and trans black populations are considered to be from outside of Africa. This work is for me a way to address the issue of homosexual and transgender identity, rejection and exclusion but also the pride of the people; among the cacophony of homophobic speech under the guise of anti-imperialism and racist homonationalism remarks quick to stigmatize an entire continent. There are the lived realities of human beings that needed to be told. Lolendo is between politics and art, with the idea of the need to think, question and the urgency to act.

MK: How have you made and still making connections with the people you photograph? You would talk about an environment or you would rather say that there are lots of very different people in different spaces?

RSK: I am an activist working on HIV/AIDS issues and the rights of LGBTI from several years now – both outside and within organized spaces. It is through activism that I got involved with DRC’s LGBTI community networks. Associations such as Gay Malebo, PSSP and “Si Jeunesse Savait” etc. put me in touch with their members to whom I explained the goal of the project, and who agreed to participate. I naturally went to them because the struggle for the human rights of sexual and gender minorities are carried by the persons concerned in the first place. There were also meetings with different people in different spaces – people from nightlife, the artistic community, social networks, etc.

MK: How is the visibility issue in a country where the news is dominated by a war where much of the violence is hidden or sparsely publicized? LGBTI people are visible in such context?

RSK: The lack of visibility of the LGBTI communities is linked to the systematic homophobia that plagues the society. Just as the lack of media coverage of the violence against civilian populations in the Eastern part of the country reflects the disdain for the human rights of women, children and men. Sexual and gender minorities have realized that visibility is very important, even vital for their problems to be taking into account; move away from the position of victims and reconsider themselves – while keeping in mind that in world’s history, those in dominant positions have never surrendered their privileges out of generosity. By “coming out of the shadows”, homosexuals and transgender refuse to be subject to systematic paternalism when it comes to expressing themselves and strongly reaffirm their refusal of clandestinity and precariousness as a result of a homophobic policy increasingly sophisticated which allows a legal vacuum, adopting no law against homosexuality while leaving the homophobic speech develop in society, in public and religious debate.

The visibility of gays reconnects with a long history of struggle for freedom and equality for social and political rights. Until now the authorized and lauder speech were only that of hatred; thus the Congolese society rediscovers recently in its street the reality of homosexuality and trans identity. The majority will never give us equality if we do not fight for it and this fight is done through visibility. Overall, it is clear that there is a growing interest in documenting the lives of LGBTI, decolonizing our bodies and minds by affirming our African identity, promoting the transfer of experience and the need to reconstruct homosexuality and trans identity’s collective memory, this is expressed with more and more insistence on the African continent.

In Kinshasa, it is not at all uncommon to recognize and meet visible LGBTI people who assume this visibility and do not wish to hide. There are two types of representation, one presented by the homophobes and another by the LGBTI community itself. In the country, we have the “Molière” TV channel which regularly broadcasts stigmatizing reports made on the basis of denunciation with the complicity of the security forces and aim to catch people in the act of homosexuality. Those reports are similar to the Egyptian raids on homosexuals that have experienced a worrying peak in 2014 – an Egyptian journalist, Mona Iraqi, triggered one of those events; she filmed a scene for her weekly television program and congratulated herself for this “moral victory”. The practice and the comments caused an international outrage. In DRC, this is done every week in a surreal silence and scorn. The politics do not create the conditions to avoid the stigma and violations of individual and private rights. Only associations feel disturbed and try to negotiate with these channels to prohibit such broadcasts but in vain for now.

There are also more and more programs motivated by the TV ratings where people from the community get interviewed even if one still feels that they are presented as freaks. There is no program with a goal to educate and inform people from a real journalistic investigative work.

According to a survey conducted in six provinces (Bas Congo, Katanga, Kinshasa, East, North and South Kivu) of the DRC by UNDP in September 2013, men who have sex with men (MSM) account for 28.8% of all the key populations (sex workers, intravenous drug users) surveyed, or 1,426,295 of the estimated size. They represent 1.9% of the general population. On average, the hidden MSM population is representative of 83% of the whole country, which means that the displayed MSM represent only 17%, and here we are not talking about the other members of the community living underground or underserved – that are the lesbians, bisexual, trans and intersex.

Joseph, District of Bon Marché, Kinshasa / DRC, 2015: “I am a computer engineer. My biggest professional wish is to create my company and live out my dream of an Africa that is modernizing in order also to serve as a benchmark of success for young gays. I am part of Jeunialissime, a youth association struggling against discrimination (focus on LGBTI). We are your brothers, your sisters, your friends, husbands and wives, but we hide for fear of hurting you. “

Claudia, Kimbanseke district, Kinshasa/DRC, 2015: “Some people say that homosexuality did not exist in Africa before colonization, others say that it existed and both sides have their arguments. Others say that homosexuality simply does not exist in DRC but when I look around me I see many Congolese homosexuals of all generations. I know without any doubt that it does not come from abroad. “

Let things be clear once again, there is no injunction to coming out or visibility, much less on proselytizing, my purpose is to explain why it is desirable, particularly in terms of public health that people should not be in hidden. I do not deny that visibility could make more precarious the economic situation of certain category of gay or trans communities. If we consider the issue of class alone, not everyone has the living conditions that allows them to come out even if the threat is present. In DRC or elsewhere, coming out and visibility are not the only way to exist and to live life fully. The univocal speech about visibility is problematic; there is no single story and I am well placed to know.

MK: In this work in progress, have you made up your mind about the kind of portrait you want to do?

RSK: I am only using the tools forged by the activist movements that fed the expression of minority speech, the speech in the first person. It is about surfacing people’s lives and struggles over time and document the work of LGBTI activists who are pioneers in the DRC. Tell a visual story of the country’s sexual and gender minorities, a kind of archive of portraits. The complexity of the task lies in the fact that I realize my work in an intersectional approach which calls for combinations of gender, sexuality, class, urban or rural environment and race – the portraits must adapt to all of these contexts. They will all be realised using the same procedure, front, side, back or three quarters particularly in order to protect the identity of people who do not wish to be fully visible.

MK: How does the VIH/AIDS question cross these visibilization issues?

RSK: The stigmatization of lesbians, gay, bisexual, transgender and Intersex (LGBTI) results in discrimination in access to care and health even as the country is one of the most affected by HIV. LGBTI people are very vulnerable to HIV/AIDS due to the social marginalization they are subject to. To put it bluntly, there is no political will to allow better access to prevention and care against the HIV/AIDS, and promote human rights protection for all categories of population or to sensitize the society in that direction. In the current context, epidemiological figures reveal that the prevalence of these communities is very important and worrying. Through having dragged the targeted actions toward these groups, we are in a concentrated type of epidemic, the problem has become important – we must conduct targeted interventions in specific communities.

Visibility becomes a public health issue; as long as LGBTI people will remain unrecognized, unprotected, without rights, without compassion, as should any human being – a torrent of hatred and unbearable ignorance will continue to fall on them and keep them away from medical and health care. PSSP is the only structure that deals specifically with key populations (Gays, sex workers, intravenous drug users).

MK: Are there festive places or associations that you would also like to show through these portraits?

RSK: I want to show that Kinshasa for example is a party town for LGBTI people; they are not left out when it comes to partying especially since the establishments have realized that they were one of the best clients. In fact I want to show all the places where LGBTI people meet, be it social, festive, leisure spaces, associations, discussion groups, club and private circles, educational and cultural worlds etc. I want to make visible the artists who by their gay friendly position boost a positive image of LGBTI people within the general population.

Regarding the religious places for example; facing the violent rejection of evangelical and traditional churches I met LGBTI people who have faith and wish to be able to practice their faith in peace, they are turning to the Raelians who accept them as they are… It is important to document all this.

MK: To conclude, it is a work in progress, so at the moment what do you need to continue your work in good conditions and give it greater visibility?

RSK: The funding is a big headache. Right now I spend more time looking for support than taking photo, what a horror! Until now I finance the project myself, in 2016 I will get subsidies that do not yet match the needs. Then there is the problem of the media that does not rush for now to give this work visibility, I guess that will happen… Finally, there is the question of safety that arises as well. There are already people who have advised that I do not to continue this work and contrary to what one might think these requests also come from the LGBTI community, people who are privileged and secure but are totally disinterested about minority rights. In Togo, there is an expression or veiled threat that says, “Do not wake up the sleeping lion”, it is used to deter LGBTI and MSM leaders who want to push the issue of LGBTI human rights through their advocacy work. The sleeping lion refers to Article 88 of the country’s Penal Code, which criminalizes homosexuality but is rarely implemented. The lion wakes up or not is not my problem, when one defends a just cause one does not care about the opinion of others, we act and that’s it. In any case, nothing will intimidate me; I will lead this work to the end.