Queering Carmen

By Claire Ba

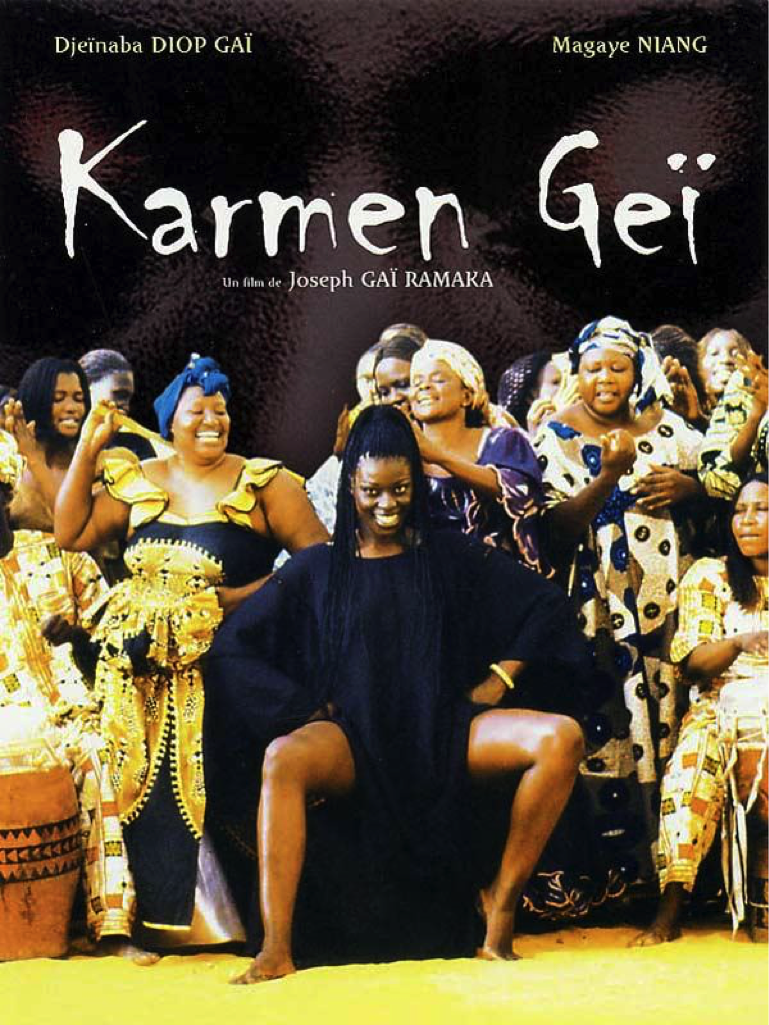

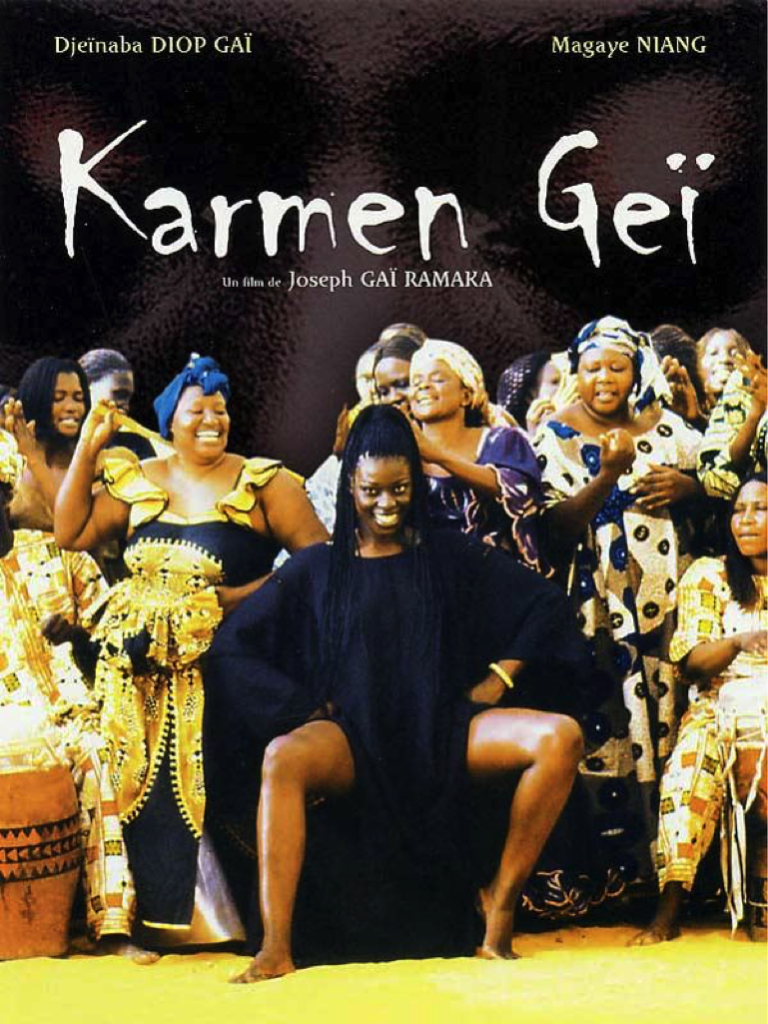

Are you familiar with Karmen Gei? This film by Joseph Gai Ramaka could be considered as much a classic as Ousmane Sembene’s Molaade. Yet, contrary to the latter, Karmen Gei seems to have trouble getting the attention it deserves. With Karmen Gei, Ramaka takes Senegalese cinema to a whole new level by producing, in 2001, the first queer, African and musical adaptation of Bizet’s Carmen. So what exactly is Karmen Gei about and why is it so seldom referenced when talking about classical African cinema?

A character from Prosper Merimee’s novella, later adapted in the opera by Bizet, Carmen is a woman who constantly struggles between a profound desire for freedom and various forces trying to restrict that freedom. Our Senegalese Carmen is no different. Embodying power, beauty, determination, sensuality and freedom in every sense of the word, Karmen Gei evolves, allowing nothing to jeopardize her freedom.

Ramaka’s film is significant for it is such a beautiful and unprecedented adaptation of Bizet’s Carmen. Indeed, he integrates many aspects of traditional senegalese story-telling techniques: music, dance, praise singing, fortune telling, and more. From traditional drum circles to the mention of various senegalese mythical characters like Coumba Castel, the protective spirit of Gorée Island, or Aline Sitoe Diatta, an important female figure in the fight against French colonization, this musical does a great job at staging Bizet’s Carmen in a senegalese context.

Karmen’s character transgresses postcolonial gender constructs in many ways, going against everything one might expect from the “postcolonial senegalese woman”. Karmen is freedom and this is manifest in the way she carries herself, her interactions with others, and even her sexuality. Karmen is very liberated and she does not hesitate to use her sensuality to her advantage and sometimes, for mere pleasure. For instance, to escape from the prison where she has been made captive, she seduces Angelique, the warden. She then has a love affair with Lamine, a police officer she kidnapped and later abandoned because his love for her was becoming too overwhelming.

Karmen does not let herself be confined by anything or anyone. Even when Angelique, helplessly in love with her, pleads her case to Karmen’s mother. Even when Lamine begs her to stay with him. Always, Karmen’s freedom comes first. Her life must and will be on her own terms. And when this is no longer possible, she surrenders to death at the hands of Lamine who, wanting her all to himself, could not fathom the fact that a woman could need so much freedom.

Her constant struggle for freedom is also apparent against established postcolonial systems of authority and oppression represented by the police. Indeed, Karmen is chased down and imprisoned several times, sometimes for no apparent reason. These systems are also represented by masculinity and sexism as illustrated by some of the comments made about Karmen. “You are quite an interesting woman” says Massigui to which she responds, “No more than other women… They just don’t show it so as not to make waves”, yet another illustration of the conflict between the desire for freedom and society’s expectations of women. For a young Senegalese woman, the choices usually come down to being true to herself at the risk of being branded, or conform to society’s expectations at the expense of personal freedom. For Karmen, the question is a non-issue and she chooses death over subjugation.

The sexism Karmen is up against is also illustrated by comments made by some of the men she works with: “She would go for anything. She devours men … it will wear her out…” As expected, nothing is said about the man she is seeing even though it is no secret he left his lover to be with Karmen.

With Karmen Gei, Ramaka draws a very different picture of the postcolonial Senegalese woman, and to some extent, of the African woman, challenging notions of power, agency, voice, and sexuality.

“Was senegalese society more tolerant a few decades ago or was Ramaka simply being bold by producing Karmen Gei?”

Sexuality is in fact another interesting theme of this film. It is obvious that Ramaka does not shy away from the explicit and the unconventional as we can see with the love scene between Angelique and Karmen or even the part showing a very masturbating Angelique. Moreover, at no point is the brief love affair between the two women portrayed as immoral. The women in the prison are all very aware of the sexual tensions that exist between Karmen and the warden and some of them even joke about attempting to use their charms to be released from prison.

It is also interesting to see Angelique going as far as meeting Karmen’s mother to plead her case; pleading to which the mother simply replies with words of encouragement and a promise to do what she can. No outrage. No antipathy. No violence. Just a conversation between a mother and one of her child’s lovers. In a perfect world, there would be nothing special about this scene. However, given the atmosphere of hostility towards LGBTQ people currently sweeping the continent, Ramaka’s work raises fundamental questions. Was senegalese society more tolerant a few decades ago or was Ramaka simply being bold by producing Karmen Gei? More importantly, what inspired Ramaka to take the untraveled path of a queer representation of Carmen? Was it a desire to represent senegalese society in all its authenticity? A need to foster dialogue? Or a simple expression of his talent and creativity? Whatever, the reason, it is undeniable that Ramaka demonstrated great originality in this first production of an African Carmen.

A deep desire for freedom, resistance against sociopolitical systems of oppression, a lesbian love affair, nudity, sex outside of the “sacrosanct” boundaries of marriage, explicit tolerance toward what many deem “deviant” sexuality, musicality, “senegality”; with Karmen Gei, Ramaka gives a unique touch to the opera Carmen.

So why is this film so seldom referenced with regards to classical African cinema? One reason may be the simple fact that Karmen Gei raises its fair share of controversy, and not only because of its liberal nature. The film was banned shortly after its premiere in Dakar partly because a particular scene generated controversies in certain senegalese religious communities. Indeed, the scene showing Angelique’s funeral is accompanied by a famous Mouride religious chant. The Mourides being one of the country’s most popular Muslim brotherhoods, many considered it inappropriate for the chant to be included in a movie like Karmen Gei and did not shy away from voicing their discontent. Obviously, the unfortunate censorship of Ramaka’s outstanding work could also be attributed to the liberal nature of the film. Nonetheless, there is no question that Karmen Gei is a work of art worth re-exploring.