Homoparentality: A Revolution Through Love

By Régis Samba-Kounzi

“A people without knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots.” Marcus Garvey

Despite abolition, African and Western societies remain marked by the transatlantic slave trade and colonization. When analyzing the experience of black men and women under slavery and colonization to uncover the particular forms of violence they faced, it can be noted that enslaved people were historically the figure of anti-parenthood; the anti-parent par excellence. Today, officially refusing to recognize same-sex parenthood is part of this legacy of dehumanization, provided we do not adopt a restrictive definition of the phenomenon. Similarly, one of the oldest legacies of the so-called “African traditions” on the continent is also materialized under the seal of silence, invisibilization and erasure, notions that sometimes lead to favoring and masking social realities and inequalities. It is from this angle on the history of slavery and colonization that I want to associate and make analogies with our contemporary family experiences as minorities.

The violence of social relations of domination on the basis of race, color, class, gender, disability, sexual orientation or religion experienced by minority groups is universal, regardless of geographic location. One of the functions of the exercise of power is to force individuals to follow norms. One of its drifts is the application of dehumanizing injunctions and rules under the guise of public good. This explains how states or heteropatriarchal societies enforce, on sexual and gender minorities, the prohibition to exist, and a fortiori, to build their own family, using any and all means to stigmatize us, pathologize us, discriminate against us, and instill in us shame about ourselves through the internalization of a pseudo-indignity and inferiority. We, sub-Saharan Africans, did not wait for slavery and European colonization to experience violence. And although customary slavery is not comparable to colonial slavery – massive, systemic and racialised – it remains an act of dehumanization.

I understood through my own childhood what it was like to experience domination as could be exercised by adults, especially when you are different from the norm they have chosen for you. So, I had to show resilience early on, learn to transgress when possible, and in turn build my own homoparental family; with the desire to do things differently, and the need to fight publicly, to give others in similar situations a sense of dignity, and to bear witness to the importance of family and childhood in one’s journey. Family roots are extremely important and I am reminded of how privileged I am, even though there is still a long way to go.

Looking back, as far as I can remember (at least the 1980s), whether in France, Zaire or Congo-Brazzaville, there have always been people in my environment whom I could associate with sexual minorities. Not all of them identified in this way, but some dared to take the leap. And the majority of these people are now parents. What I mean is that homoparenting, in Europe as in Africa, is not new. What is new is visibility; it is the fact that it has become a political issue and visible as such in the public arena, especially in the global north, in South Africa and in South America.

I became a homoparent in the late 80s, when I was 19. My daughter, Lolita, was born of a classic sexual relationship with a heterosexual woman. There was no “plan” of parenthood. It was, as they say, an “accident”. But it was my shame at being homosexual that pushed me to have this adventure. I wanted to prove to those around me that I was heterosexual. I fell into the trap of denial. I also became brutally aware of the dangers I had exposed myself to, driven only by family and social pressure and the human need for acceptance. And the first questions were whether, in addition to a future birth, I could have contracted or transmitted HIV.

A lot of questions would obsess me later on. At that time, there was no treatment. AIDS was a death sentence. And this is still the case today in some regions, particularly in Africa, for the millions of people who do not have access to medication due to lack of funding, but above all lack of political will. I had family members who were HIV-positive and had AIDS. Some of my mother’s employees were also sick. It was then that I decided to get involved, without imagining that it would become my life purpose, that it would lead me to Act Up Paris, an anti-AIDS association founded by the homosexual community. As a young adult, I was interested in agriculture and food sovereignty issues in Africa, like my heroes at the time, Paul Panda Farnana, a Congolese agronomist and nationalist, and Amilcar Cabral, a revolutionary from Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde. But most of all, what I had come to understand was the importance of carrying my own dreams and making my choices respected.

I joined Act Up in 2000, and it was in this organization that I finally created my chosen family. In 2003, Claire, Julien and I, then activists and employees of the association, spoke for the first time about the desire to have a child. Our parental project took time to mature. And two years later, our son Tiago was born, conceived via home insemination. Conceiving our child under these conditions was illegal and punishable by two years in prison and a 30,000 euro fine. The dehumanizing system in which we lived could not stop us from freeing ourselves like others before us.

Our homoparental family simply shows that individual trajectories have always flouted society’s injunctions, and that nothing abolishes the will, the desire for parenthood, including for homosexuals or trans people. The system cannot abolish agency, our ability to be actors of our own lives.

And, contrary to what one might think, the desire to build a homoparental family does, in no way, mean wanting to adhere by mimicry to heteronormativity. Rather, it is about wanting to raise children, and transmit revolutionary values to break the constructed idea of a one-size-fits-all, classic family that all of humanity should model. We are teaching our son to be free, to think critically, to be respected. His very conception was a cry for freedom. He comes from profoundly free people; people who exercised their right to be themselves by demonstrating civil disobedience, by defying an unjust law, by refusing the prejudices and the “what-ifs” that prevent the truth from being told, and by having a public discourse on the subject, without shame, and without giving a damn about respectability. Whether our families are visible or invisible, when they foster, through children’s education, open-mindedness towards restorative imaginations through principles of equity, equal rights and diversity of families, acceptance of differences, in short, other ways of inhabiting the world, they participate in the transmission of our personal and intimate experiences, and transform the world into a world of human dignity.

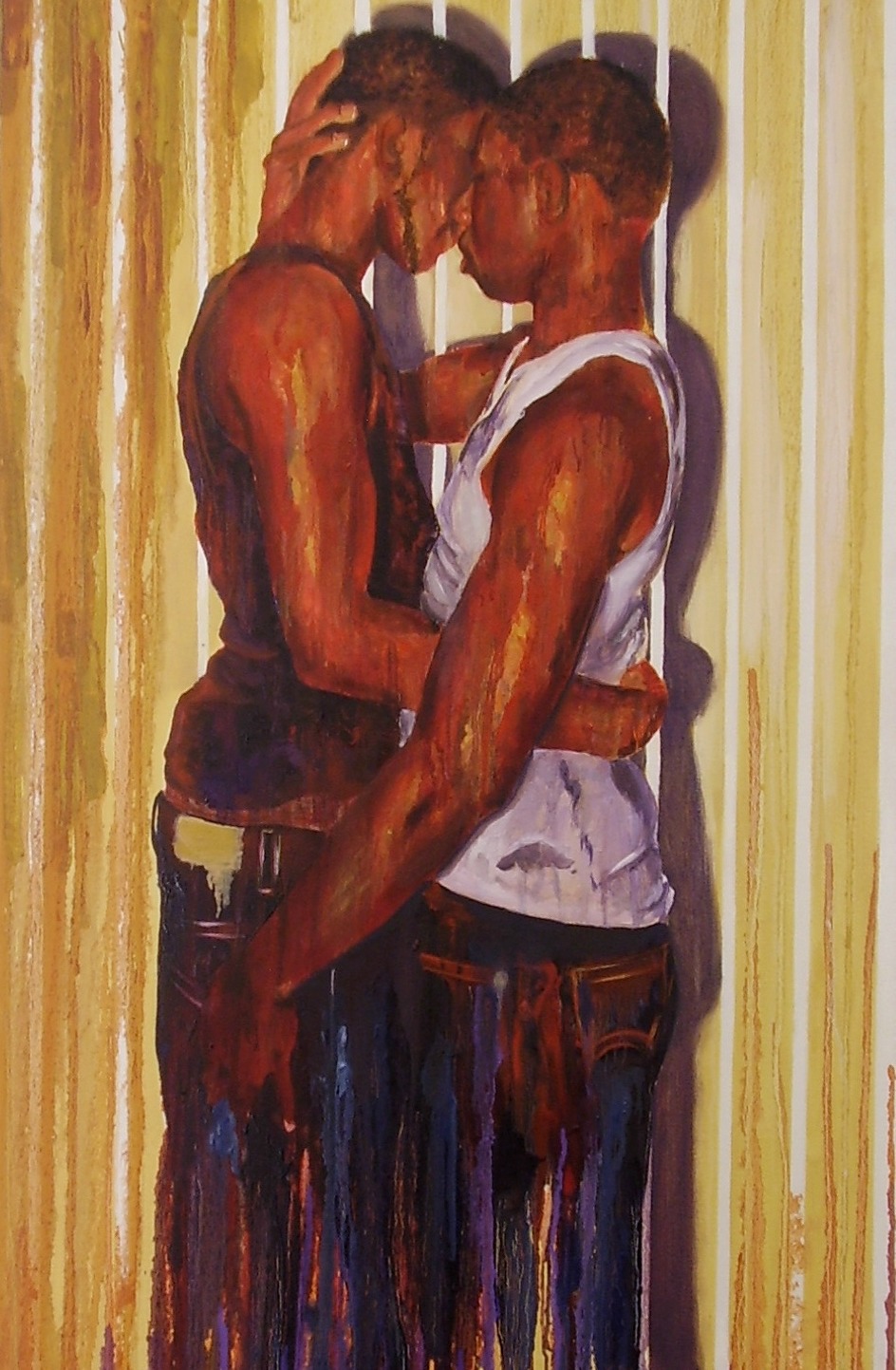

From this experience, I wanted to use creative photography as a tool to fight against the erasure of our experiences, through the production of situated knowledge and the generational transmission of the memory of empowerment and agency tools. The “Bolingo” series, started in 2010, was born from this desire to break the silence and fight against invisibility; to reclaim art as I have reclaimed my sexuality, my family and my politics; to show simple but emotionally charged moments, with our loved ones, our families, of blood and of heart. It was necessary for me to denounce the lie, proof that legality is a matter of power, not of justice. It is because we have a homophobic, transphobic and hypocritical dominant order that we end up with a liberticidal law targeting homoparental families in the Congo-Kinshasa constitution. If there was real justice and if we were in a democratic country, such an article would never exist. If the arts and culture have raised my social and political consciousness, if they have changed my view of our society and its inequalities, then they can do so for everyone. The role of the artist and the activist, of the artivist, is to make sure that no one ignores the world we live in and that no one claims ignorance. Art and photography make it possible to expose, to break the silence, to give a face to marginalized people; those whom we are not supposed to talk about, whom we absolutely do not want to talk about, whom we want to make invisible. The simple fact of talking about ourselves, of describing our wounds, whatever they may be, pays tribute to our dented paths and underlines that multiple possibilities are available to us. It is essential to seize this opportunity. Reclaiming the narrative has helped me to begin the journey towards understanding my own story, way beyond the photo series I produced.

Bibliography

Aurélia Michel, Un monde en nègre et blanc. Enquête historique sur l’ordre racial, Paris, Seuil, « Points », 2020.