Obsidian

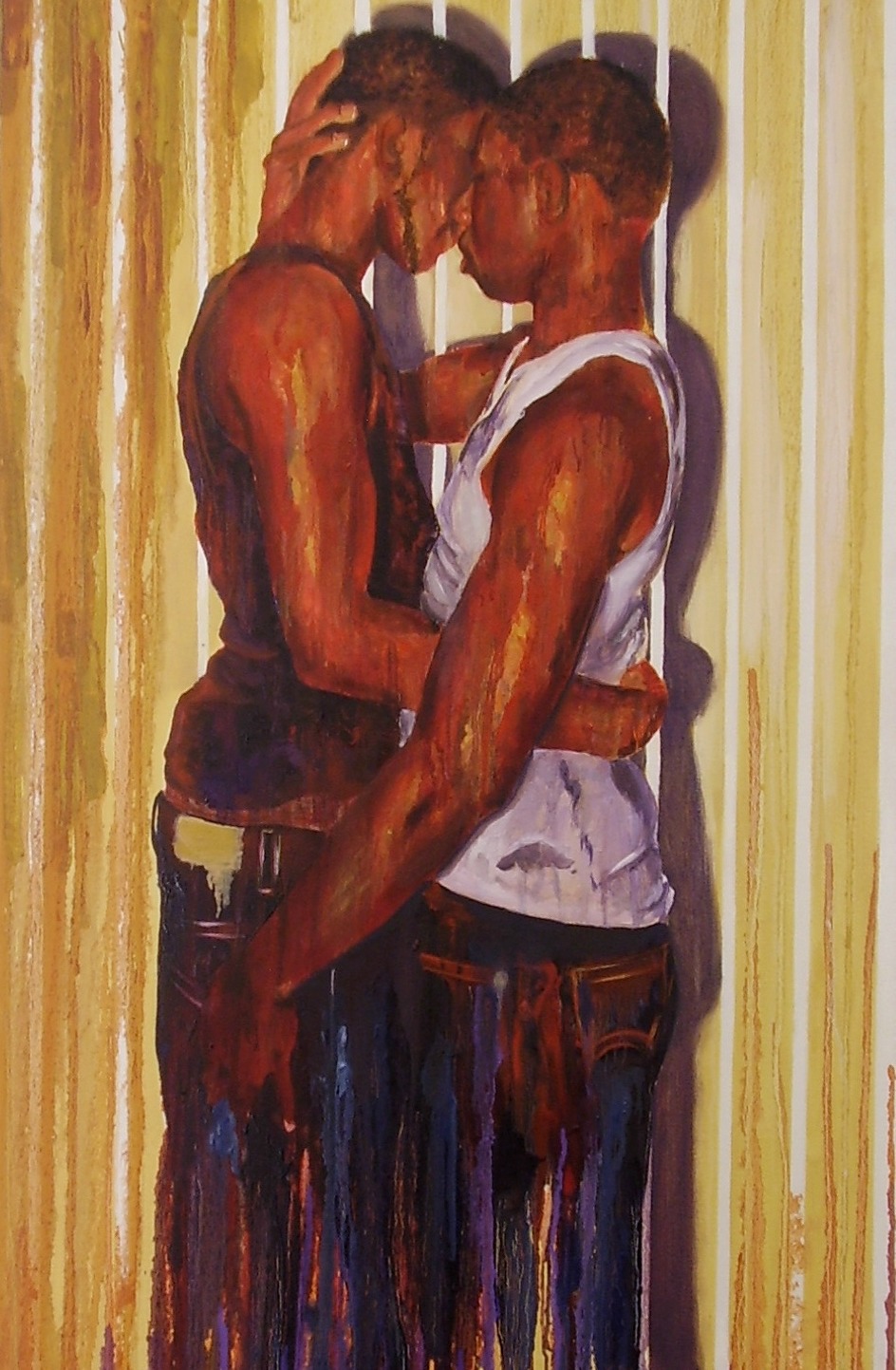

By Ashley. Photos by Siphumeze Khundayi

In the South where she was from, where nails dug water from the soil and women were unsung magicians and their daughters riddles, there, love was not simple. Love was not uncomplicated. The trouble, she found, was the insufficient warning signs on the streets, and the blamelessness in the light city air. And there were simply not enough cracks in the pavements – things are always better with broken tar.

You have to tell me. The words stayed, bounced on the walls before returning to her, new and full. She put her arms around Malika, and just then the sun crept in through the window and searched the space out like a prying trespasser – then settled on Malika’s face like she was a morning. Malika turned. Her eyes were sharp on Haoa’s face, as if scrutinizing it for the words that almost fell out. Haoa always held back – Malika did not bother herself with this until they had sex, and then it changed everything. It was as though her eyes were open for the first time and she really saw – maybe love was only blind before consummation.

You have to tell me. Malika had whispered the words. Looking at Haoa’s face did not reveal what she needed to know. On it, she saw useless things. From the scar on her left cheek – a thin streak that looked hand-drawn with heedful artistry – she saw Haoa falling off a tree as child. From inside her eyes – the hazy balls that darted from corner to corner and found nothing gaze-worthy – Malika saw a scared little Haoa, she saw how her lower lip trembled when she was nervous. She was nervous as frequently as her nostrils found new breath – as frequently as the breath seemed to catheterize her mouth of language.

The truth was not simple. If it was, Haoa had no taste of it. She knew what she knew, what she could not trust herself to pour out accurately. She could not be sure of her account anyway – not without the testimonies of Tlatsi and Motse, her childhood friends who witnessed it all with her.

Haoa had more than the bargain of friendship. When Shoane was her aide and the fabric of her ribs, she had true, filling companionship. They were inseparable, like the contents of mature wine. Their kinship had its bumps, but you don’t feel yourself falling in quicksand.

Shoane had sat beside Haoa in standard two. She was new at the school. She smiled at Haoa with the width of her teeth. Everything about her was perfect. She had lively eyes, her nose was a small knot with seamless little pits, her cheeks were full and round, her ears hovered on the sides of her face – as if detached from it. Her lips were her best part, the lower lip was thicker and fuller than the thin, artistically delineated upper lip. Haoa decided that she had a masterpiece of a face, unmatched by all else save for her handsomer spirit. If Shoane was a day, she was the sun cracking its way out before the chickens crowed, flickering through trees and finally steadying on soft soil. She was birds singing, butterflies carrying on their preoccupation of beauty, bees going about stinging sweetness, bumble bees buzzing free and wild – as wild as a fat bee can get. She was water springing from sprinklers embedded below the neighbour’s greener grass, an afternoon on the hill, watching the sun fall off the edge of the sky, slow, slow. And then watching how quickly the night ate the light and would not burp it until the next dawn. She was a night’s sleep in the lulling whoosh wash of a gentle rain. If Shoane was a year, she was one of plenteous rain, many brilliant sunsets, fruitful trees, snow in the winter, and an autumn of jazz on the radio. Warm days and colour everywhere.

Shoane and Haoa’s friendship must have begun long before that day. Shoane’s incomplete smile must have been the pressing of an activation button to bring to life a friendship that was already written in the stars because, after that initial interaction, they were passing notes and making plans for sleepovers at Shoane’s grandmother’s house.

Shoane was the youngest of eight orphaned children living at her grandmother’s house. Her mother had run away from home at sixteen with a boy from Sibi – a village to the north of her own – fleeing from the old suitor chosen by her father, only to return on a deathbed in the back of a van with a baby – Shoane – growing in her womb. When Ame died, her mother had no choice but to take care of Shoane – who despite trying hard, she could not see. The orphans were eight times a reminder of failure and humiliation, the failure of Ame’s mom to give her husband sons. The humiliation of having one runaway daughter, another who failed utterly at marriage and only angered her husband and aired their tiffs in uncovered bruises all over town, and two who were likely to have killed their husbands with disappointing behaviour. The four of them brought home shame, and then sons and daughters who they would leave when they died, one after the other.

It was Shoane who was the biggest symbol of disappointment. Her mother had died first. Her father is said to have died on the streets in Johannesburg before Ame returned home on her back. Shoane’s grandmother looked at her with worry for the day her own demons would come out to destroy them all. She was a widow then, with a divorced daughter, two widows and eight grandchildren who were all estranged from their fathers in one way or another.

Even after the rest of her children had died, it was still Shoane’s face that had the power to turn her mood foul at any point. Shoane was too young to understand why that was. Even when the other orphans ostracized her, calling her Ngoana Letekatsi[1], she could do no more than find chores out of everyone’s way and be so quiet she was sometimes only remembered during dinner, when her grandmother served porridge and gravy in the eighth plastic plate.

“Sha!” she would yawp, as if saying her whole name was bothersome. She would pull her nose and squint at Shoane’s face, then throw her the plate when she was barely close enough to catch it without diving to it. “Get out of my way Sha ‘nake, get out of my sight!’ she would shout thereafter, “I cannot deal with all of you orphan bastards.” Shoane would walk out steadily, only to break into a run when she had left everyone’s penetrating eyes behind. She would get to the tree at the bottom of the toilet and sit quietly under the safety of its wings to eat. Her eyes would water when she tried to picture life in the care of her mother and father.

For the longest time, Shoane had nothing but that tree and the big, wide sky in which she threw wishes as a ritual. Until one day a social worker came by her grandmother’s house and warned her about keeping Shoane out of school. Her grandmother’s young friend Mosele had gone to see the social worker about providing education for all the children in her care except Shoane, and the social worker had

come within two days to see her. “She has to get an education. Every child in this country should have access to education, do you understand ‘MaLefa?” she had said. Shoane was sitting in a classroom the very next Monday, smiling anxiously at the odd-looking, stammering girl beside her per the social worker’s order to make friends with your classmates; smiling is a good way to declare your interest in someone, so smile and invite them to sit with you during lunch break.

[1] Whore’s offspring

By the end of that week, Shoane knew every corner of Haoa’s house, the pale-white kitchen with its four-plate gas stove, its beige plastic tiles, the rectangular table on metal legs, its matching chairs, the Hart pots, colourful tableware, and white organza curtains. She knew the living room, its pink walls, brown sofas, 52-inch round-screen television – the black and white motion pictures on the television, the dark oak room divider, the radio in its spot on the divider, the record player next to the door. Haoa’s father’s records were stacked close to her mother’s sewing machine, which sat next to the large window. There was a pink carpet on which sat the coffee table, carrying books. Haoa’s paintings decorated the walls like prized art. They were so stunning and brilliant in Shoane’s eyes that she needed to know all there was about them – who the painted boys were, how often Haoa saw them, where they lived, what language they spoke, where Haoa had learned to paint like that – and Haoa, not being too modest to talk about her work, poured out their names without failure or stutter. “This is Motse,” she said boastfully, pointing at the face of the tall boy, “and this short one is Tlatsi! He is a painter like me!”

They were not allowed into Haoa’s parents’ bedroom, but they found themselves there enough times for Shoane to note the tall oak wardrobe, the maroon velvet headboard, the red bedspread, the maroon carpet, the black bucket hanging on a nail on the side of the wall, the window and its white organza curtains, Haoa’s mother’s shoes tucked beneath the bed. She could find Haoa’s room blindfolded, and in it she could point to the thin, low bed. The white wardrobe on the side of the bed, three of Haoa’s paintings scattered on the wall – other illustrations of her favoured models – the bucket face-down beside the wardrobe, Haoa’s shoes hiding under her bed, the khaki mat.

Their friendship was a whole new life for Shoane. Her grandmother, being a wolf in full-white sheepskin, could not be mean to her in the presence of Haoa, and Haoa was present every single day – even on stormy summer days – and by the time she left at sunset, Shoane had had dinner and was ready to sleep.

During the weekends, the two of them would convene as early as the first crow at Shoane’s gate to begin their chores. Haoa had no chores at home, as her mother had hired a helper so that she could focus all of her energies on her sewing business. They would start with the laundry. Shoane would hand-wash, and Haoa would rinse and hang the clothes. And then they would move on to the dishes, then to sweeping, dusting, and scrubbing the floor. Haoa was the quickest to finish her share of the chores every time and always told Shoane that Tlatsi and Motse had helped her.

One day after their chores were complete, they packed Shoane’s pyjamas in her school bag and walked to Haoa’s house in the village centre. On their way there, they met a group of young village girls who were infamous for their churlishness.

“Haoa ‘nake, you are still friends with Shoane? You know, I never saw it coming. What ever happened to those ghost friends of yours?” said the gang leader, laughing, “How did you get a real friend? Tell me Shoane ‘nake, don’t you get tired of waiting for this stammerer to finish stammering her greetings?”

“Leave us alone, Rebecca,” Shoane responded.

“Uh! The orphan orders me to be quiet, how nice? Is it young love Shoane ‘nake?”

“What are you talking about?”

“Just so you know, we’re not blind. We see you both carrying on like lovers. Anyway… I was just trying to warn you Shoane ‘nake, this friend of yours is not stable”

“You are th…the crazy wa…wa…one!” Haoa snapped and spit hot saliva into the warm spring soil. They were thirteen and closer than any intimacy shared between friends.

“Haoa motsoalle, what did that Rebecca mean about us acting like lovers?”

“She is cray…crazy”

“Yes, I know that. But is it wrong that we… you know?”

“I d…doh…don’t know Sha…motsoalle oaka, I don’t think so. F…father says-”

“Ame’s mother says that I have to get married soon, because I am a woman now and I can have children and a husband of my own”

“Is that wha…wha…wha…what…what you want?

“I don’t know”

“F…father says that whe…when you love someone, you…you…you show them th…that way. And I l…l…love you, like I love Father”

“I don’t think I am comfortable with you loving me that way Haoa motsoalle, I have been talking to aunt Mosele about things and she told me that it is wrong for your father to do… with you”

“You spoke to Mo…Mosele about me?”

“Well, yes Haoa ‘nake, she is my friend…”

“I am your…your friend Sha ‘nake! I love you. I know…know you. I am your f…friend.”

“I know. Please just listen to me. Okay? Calm down”

“Okay”

“I love you Haoa ‘nake, you know I do. I love you with my whole heart. I don’t love you like I love aunt Mosele, I don’t even love you the way I will love my children or my husband. I don’t love you the way your father loves you, or the way you love him. I love you, love you. If it was okay and normal, I would marry you and have children with you. But aunt Mosele says that it is wrong for me to feel that way about you and that if people knew, they would burn us both.”

“It’s f…f…fine! Go and marry a husband and have l…l…lisping, b…blind children. I don’t care. I am g…g…going to marry Father when mother dies.”

“Haoa! Why would you say such a treacherous thing? You can’t marry your father, that is unthinkable!”

“Says who?”

“The Bible?”

“I don’t care!”

“Haoa!”

“Wha…what? You are going to leave me Shoane! You are going to leave me here, with F…f…father and her and I wo…won’t survive it! Have I not been g…good to you motsoalle? Why do you want to go away from me?”

“I don’t know…”

That night they slept quietly – all the lines of normalcy had been blurred many years before that night – with their legs entwined and their breasts bare. They both dreaded what would come in the morning, what awkwardness they would find during breakfast, how they would explain their apartness during the day and how they would run into each other at school and greet each other like strangers. They were sure that night that they would never speak again, or be in love the same way. They were wrong. They found love’s unbelievable mercy. How the very next day they woke up and had I’m sorries falling out of their mouths. How they hugged and swore never to separate, never to let anything get between them.

The year they turned sixteen, Haoa’s mother inhaled so much gas that her body turned red and white. It was their helper who found her on the kitchen floor. Her pink nightgown clung to her small frame. Her eyes wide open – the way Haoa sometimes stared into space and stammered incoherent things – her face was paler than an empty sky. For most of her life, she had been an empty sky. She was married to Haoa’s father at fourteen and did not have a child until she was twenty, having been considered helplessly barren. Haoa arrived too late, Haoa’s mother always thought, when she watched her daughter chasing flying insects and chattering away in her lonesomeness. She had waited too long for a child and by the time her water broke, none of her other parts worked. She wished she could have loved Haoa the way she saw mothers loving their children, the way she heard mothers calling their children home at sunset, the way they nursed their small babies and baked cookies when their teenagers married. She was a gaping hollowness – a vacuuming hole sucking in any joy in her vicinity – and like ouroboros, she consumed her own self. They buried her on a windy spring day.

That year, Shoane was requested for marriage. Her suitor was a widowed man in his late fifties. He earned his living running a postal business. He lived in a humble two-bedroom home in the heart of the South. None of this was much, but it was more than Shoane had wished for. She was close to the blissful simplicity she had always wished for. She had a house of her own, a husband of her own who had no unreasonable expectations of her – in fact, he had wanted to get her a helper to look after their home, but all the people they spoke to did not know anyone who would be interested in working for them. He did not ask her to dress “more grown up,” as was often requested by husbands of younger wives. He did not ask her to stop going to school or to be back in the house before sunset. He did not even ask for sex until they were married three months.

It was a Friday night in mid-January heat. Shoane got home early from school and made rabbit curry – her husband’s and his daughter’s favourite. She had wanted to make nice with her, since the girl had not said a word to her since she had moved into the house. But the dinner did not pave a way to her stepdaughter’s heart. Instead, it left a taste in her husband’s mouth for her. And later that night, he had her. It was the first time she had ever been with a man, and it hurt her. It felt like betrayal, and it broke her heart, so after she finished her wifely duty that night – seeing that her husband was fast asleep – she snuck out of their bedroom, tiptoed into the hallway, and found memory lane. She ran her fingers over the wall and remembered its texture from back when she was ten, when she would be hiding there or passing through in haste. She opened the door to her stepdaughter’s room, rushed in and closed the door behind her before pacing to the bed where the girl sat up, looking absentmindedly into space while rocking from side to side. The moon was full and shining through the curtains so that when their eyes met, they saw each other.

“It has been three months. I can’t give you any more time. I need you to speak to me. Phephi hleke! Ke e etselitse rona – nna le oena[1]!” said Shoane, kneeling before the bed with tears rushing down her face as though her eyes were a stream of hot water. “Please say something! Please… I am begging you, please say something!” she cried.

“N…N…no!”

“Look at me, please look at me?”

“No!”

“Please Haoa, u motsoalle waka wa hloho ea kgomo”

“I am n…not your friend!”

“Haoa, I did it for us. The only other man who had any interest in me was all the way in the city. He would’ve taken me away from you. I couldn’t do that Haoa, I couldn’t have lived through being ripped away from you. I couldn’t!”

“You…you should’ve gone!”

“Haoa ‘nake, I am sorry”

“I hate you, for…for…forever!”

“Please don’t say that? Please please?”

“G…g…get out!”

“What did I do? Haoa, I just wanted to be close to you. Can you not forgive that? I don’t love your father – I love you. I want to go to bed with you every night and wake up to your perfect face every morning. And it will be that way, your father has aged. Soon he will die, and we can be together. This way, no one will question us, because we are a family now…”

“You…you want to ki…ki…kill my father?”

“No, Haoa… You are misunderstanding me. You are taking everything all wrong. This is not how I meant it, I didn’t mean for it to be like this between us. I was so sure I was doing the right thing.”

“If you kill ma…ma…my father, I will ki…kill you!”

“Haoa!”

“I will! I will!”

“Ao Modimo!” cried Shoane, clutching on to Haoa’s legs from her knees.

“I want you to…to leave! Teh…take everything that is your…yours and leave!”

“Okay.”

In the morning Haoa’s father left for work as usual. Shoane was already packed before he had disappeared up the hill on his way to the post office. Haoa watched as Shoane carried her suitcase on her head and left. She felt her heart swelling through her chest, felt her blood boiling and freezing all at once. She wanted to appear steadfast and unbothered, but her eyes filled with tears that soon fell onto her cheeks. She could no longer stand the sight of Shoane leaving – leaving her – so she banged the door shut and fell against it and wailed uncontrollably. She stayed there for the rest of that day and only got up to open for her father. When he asked, she only managed “she left”.

Shoane cried her whole way to Mosele’s house. She arrived at the door to the modest mud house and dropped her suitcase before Mosele got to the door. She stayed in that week and cried. It was the kind of loss that was inconsolable – not like hearing that her mother died when she was a baby, that her father died before he met her. It was a familiar dagger rummaging through her heart. It was the love she held dearest spitting in her face. It was a sword that she had polished and shined, slipping in and out of her chest like no matter. She was sure she would die. She could not breathe, she had an unending headache, she had paralysing chest pains, and although she worked through the pain, she thought she was dying slowly.

It was nearly three weeks after she had left her husband and the love of her life. Mosele urged her to try and get out of the yard, so she went for a walk and found herself on the rock she had sat on with Haoa many times, looking down at the stream of blue water below, throwing stones and leaves and stealing kisses in between eating grapes. She looked down, and the previously clear water was as foggy as her life, and she was inundated by how quickly things had changed. Life was like tiptoeing on a mere string that could snap at any point and throw you into the deep end without any egress. She remembered one knowing her way around her life, but now she had no idea what she would do. She wished she could go away – be on the next bus out – but where would she go? She could not bring herself to face Ame’s mother and her scorn. She had no plans of seeing her, ever again. Not after she had been so proud of her for getting a husband – she would hate her again. She could not even stand the thought of the shame. She thought about Haoa, how cold she had become. She wished she could turn back the clock, unmake her mistake. Unbreak her own heart and Haoa’s, but she had learned too many times that time, like words, was not a finger you could pull back. She had just risen to her feet to walk back to the hut when Haoa came pacing in her direction.

“Haoa!” she exclaimed.

“You we…witch!”

“What have I done now?”

“You…you bewitched him! He wo…won’t eat, he wo…wo…won’t sleep, he won’t s…s…speak, he wo…won’t look at me, he won’t tah…tah…touch me – it is your fault! You…you took him from me!” she yawped, and all too fast her hands had pushed Shoane off the rock. Her heart broke before she heard the cracking sound of Shoane’s bones shattering at the bottom of the stream. It was loud and clear, like the world breaking in half and everything falling into the crack with quick-passing sound effects. And then it was stiller than Haoa had ever known the world to be. She looked around. Neither Tlatsi nor Motse were insight. “What have I done?” she cried. Tlatsi and Motse had been wrong. They had advised her to find Shoane and strangle her for taking her father away from her. They never liked Shoane – they had been telling Haoa to do gruesome things to her since they were little, but she had loved Shoane too much to hurt any part of her – until that day. They had spoken too loudly, and she got anxious. It was a mistake. It was a mistake, she thought as she watched Shoane, pale and still on the surface of the water.

Haoa ran home wailing, wearing her hands on top of her head, and found her father in the kitchen preparing their dinner.

“F…f…father! I have dah…done something really b…bad! Please heh…heh…help me!”

[1] “I am sorry, I did for us – you and me”

Haoa was finding that the city was no place to run from your skeletons. She wondered if there was a place in the world she could run to hide from the sobriety with which she remembered Shoane. The image of her crying that night before she left. The subsequent image of her lifeless body below. Haoa missed Shoane in an inescapable way.

The city was no place for stories like hers. She wished she had been warned that if you should ever get away from her kind of past, it would not be in the city, where you met foreign girls who made you want to tell them the truth about yourself, even when the truth was that you once were in love and now you were empty and near dead. The city said that love was simple, but Haoa had no knowledge of that simplicity.

Malika stared into Haoa’s eyes with shock frozen across her face. “She married your father? Oh my god! I am so sorry, baby! And then what happened? I am so sorry!”

“She…she killed herself”

“Oh my god!”

“It was really hard on my father.”

“I can imagine… I am so sorry – for him and for you, of course, but she… she deserved it. Such betrayal!”

“She…she didn’t. She really didn’t.”

“But baby, she married your father! Do you get how sick that is?”

“We…we should t…t…talk about sa…something else, please.”